Welcome to Antarctica: with school closed, the world is a classroom

Since the beginning of 2021, Jessica Espinoza Fuentes has been working with experts at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaiso (PUCV) in Chile and teachers from Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru on designing the “Experimento Blended” program, which is part of the STEM Education for Innovation education initiative. For the past year, she’s been teaching 37 primary school students who she has never met in the classroom. But with Google Maps, they have traveled together all over the world, to places like Rome and Antarctica.

»STEM education is incredibly important for developing empathy, increasing confidence, and developing the ability to communicate.«

Jessica Espinoza Fuentes, teacher at Liceo Eugenia Subercaseaux in San Sebastián, Chile

The COVID 19 pandemic has made the need for digital teaching and learning materials in school lessons undeniable. Figures from UNESCO indicate that some 160 million students in Latin America alone were impacted by school closures. In response to the need for urgent action, Siemens Stiftung joined forces with partner institutions and education ministries in Latin America to launch the STEM Education for Innovation initiative. With financial support from Siemens Caring Hands e. V., the initiative enabled access to innovative educational formats for STEM classes in seven countries. A series of interviews with educators provides a glimpse of how everyday life has changed in kindergartens and schools.

STEM Education for Innovation

Learn about the 14 projects in the Latin American STEM education initiative.

Jessica Espinoza Fuentes is contributing to the design of the Experimento Blended program within the STEM Education for Innovation education initiative. She also tests new methods and concepts every day in her primary school classroom. She has led virtual journeys to Antarctica that explain to her class the difference between water, snow, steam, and ice; or research trips that have children exploring their environment and solving problems. A project on extracting water from fog has been awarded multiple prizes and turned one of her students into a research hero.

New methods for teaching STEM

I’ve been a public-school teacher for decades. My formal training is as a language teacher for ‘lenguaje’ – forms of expression – and Spanish. But over time, I drifted into teaching science. In Chile, this is possible through a program from the Chilean education ministry called ICEC, which implements certified continuing education on STEM and didactics through active methods at universities.

But over time, I drifted into teaching science.

I’ve been working with the Experimento program for several years now, and I must say: it’s absolutely wonderful. The inquiry-based learning methods are excellent, and the experiments can be implemented quite well in classroom lessons. However, there is a problem: Teachers in Chile – and I see a similar problem in the rest of Latin America – are under a lot of pressure to stick to the curriculum established by the education ministry. We must get through the material for every grade level, which often doesn’t leave much room for new integrating new approaches to daily lessons that are project-based, research oriented, or designed for groups. We are all interested, for sure, but we lack the mandate, time, and energy. I quickly realized that an adaptation of the Experimento program made a lot of sense.

It is necessary to give teachers help in connecting the modules and experiments to our curriculum and teaching units. This means developing handouts specifically for Chile and Latin America that make it easier for teachers to pivot away from direct instruction teaching methods and toward guided and active group lessons. My colleagues across Latin America have chosen similar implementation methods, which I have seen incorporated into the development of Experimento Blended modules. This project is certainly going to be a useful tool for schools, which are becoming more and more hybrid anyway.

Experimento

Our international educational program Experimento offers training in methodologies, teaching materials and specific experimental materials for all ages.

The COVID-19 pandemic

I’ve been working at Liceo Eugenia Subercaseaux school in San Sebastián for three years. I have 37 students, and we have yet to meet in person at the school – they are all still closed due to the pandemic health regulations. Instead, I connect with the eight to nine-year-olds online.

Not all of my students have access to the internet, but they are increasingly getting online with their own mobile phones or by borrowing one from their parents. I spent the first weeks asking acquaintances if they had computers or mobile phones that they could donate. I also got the city to provide mobile access to the internet.

I have 37 students, and we have yet to meet in person at the school.

Experimento Blended, which connects analog and digital content, is something I was using daily before it was given a name.

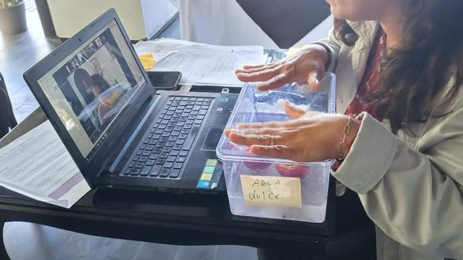

Experimento Blended, which connects analog and digital content, is something I was using daily before it was given a name. Although the Experimento kits were developed for classroom lessons, I invested a lot of time in creating ways to use the experiments in online lessons. I try to be as entertaining and diverse as possible when it comes to connecting science and language instruction. I always look for ways to show the children something surprising on their screen as we go through our daily lessons.

My experiences are now being integrated into the media package for Experimento Blended. I think it’s great that this project, which is part of the STEM Education for Innovation education initiative, is an opportunity for co-creation among teachers, university researchers and education specialists. Teachers like me know what works and what does not because we have been using combined teaching methods with our students during the pandemic to provide them with life-like learning opportunities.

STEM is universal, but it is much easier for children to learn when lessons are connected to things they know from their everyday environment. They learn to understand where they live, how they live, and what is important for a healthy, sustainable, and conscientious coexistence – between humans and each other, but other between humans and nature. This creates a much stronger and closer bond to the children’s own lives.

On a (virtual) trip around Chile and the world with STEM

Recently, I said: “Kids, today we’re going to learn about water and its different forms. We’ve been invited to the Chilean Antarctic Territory by the head of the base there. It’s really cold, much colder than it is in the morning in Sebastián when the ‘vaguada’ – thick coastal fog – winds its way through the streets. Everybody needs to dress warm. Don’t forget your hat, scarf, and your winter jacket.” One by one, I held these items in front of the screen and saw the children do the same.

Everybody needs to dress warm. Don't forget your hat, scarf, and your winter jacket.

He took the children outside in the snow and the ice.

I called the head of the Antarctic base and he joined on Zoom. He said hello to the children and used his camera to show them the base and the research projects they are conducting. Through the online meeting, he took the children outside in the snow and the ice. He showed them the weathervane, explained where the energy comes from to heat the base, and described how a person needs to behave in Antarctic conditions. He taught the children about the different forms water can take – liquid, steam, ice, and snow – and about water and temperature, all while sharing a little bit about life at the southernmost point in the world.

Before our time, how did our ancestors live? That is another question I want to address in my lessons by emphasizing agriculture, the cultivation of fruits and vegetables, our ancestral way of life, an understanding of ‘hunter gatherers,’ and the history of Chile. “Today, we are scientists,” I said to my students, “and we’re going to get to know our surroundings a little better. We are going to look at where we are from and where we live. Put on a hat or a cap, grab a magnifying glass, and let’s go.” The magnifying glass came from the Experimento kit, which I had distributed at the beginning of the year.

Today, we are scientists, and we’re going to get to know our surroundings a little better.

I said: “Today we are going to the museum on the history of the Llolleo culture. They lived in a huge area back then – from the north to the central zone, where we are, and for hundreds of kilometers to the south. This was centuries before the Spaniards came.” We connected to the museum curator, who led the children through the different rooms and areas of the museum and explained a lot of interesting things.

These virtual trips make time fly during the lessons. The children and the parents really like them. At the same time, these ‘field trips’ raise questions, which can be explored during lessons and by using experiments that are aligned with the curriculum.

I’ve taken my primary school students on trips all over the world with Google Maps, to places like Rome and Paris. There are no borders anymore. Combining “hands-on lessons” with the Experimento kit, an internet connection, and the screen has enriched my lessons with additional methods and subjects.

I've taken my primary school students on trips all over the world.

Chile’s water problem

Why does a water truck have to come to provide us with drinking water, even if we have the ocean right here?

The Humboldt Current draws a layer of coastal fog high up the coast every day. It is particularly cold and damp in winter and lies in a unique climactic zone with endemic plants and animals. The children and I explored this phenomenon together in the lessons.

One of the guiding questions was: “Why don’t we have any drinking water in our zone? Why does a water truck have to come to provide us with drinking water, even if we have the ocean right here, and the fog creates water droplets on plants, walls, and even our skin?”

This is a big problem in Chile. We are running out of water and have been experiencing a drought for years. The number of water sources is sinking, and climate change is causing several other changes.

My students turned this into a topic for their lessons. In San Sebastián and in the surrounding areas, there are also areas known as ‘tomas.’ They are settlements of families who build huts on unused land and live there. In these ‘illegal’ places, there is no canalization or electricity, until the government makes the area legal and provides basic services and infrastructure. This is one reason why water is such an important and growing issue in the region.

Success stories

I remember one student named Yeremy. he was on board right away when I suggested he should do research projects in class. One project focused on the idea of capturing clean drinking water from the fog.

This idea turned into a group project led by Yeremy. Two years later, he and his fellow students Lorena Troncoso and Matilde Rubio had created a prototype that caught the attention of inventor and entrepreneur initiatives in the school.

One project focused on the idea of capturing clean drinking water from the fog.

The project, “Free Water for Life,” won the INNOVA prize and qualified for the Congress Regional de Explora. It took second place at that competition in the “regional inventors” category. This award earned him a space in the Despegar program in the Alcubo classroom.

Another school project was research on an endemic plant that is quite rare and only grows in certain areas of the coastal zone. “Do you know about Astralagus trifoliatus? It’s an environmentally-protected plant that is threatened with extinction. It only exists in our zone. Who wants to find it?”

We took a walk on the beach with the students. The waves wash up a lot of kelp, especially a type of algae that is called ‘cochayuyo’ here in Chile. It’s traditionally used for soups and salads. The ‘algueras’ – this is the name for women who gather the algae and sell it at the market – are part of the image of the Chilean coast. But the women don’t earn much through the sale of the dried algae.

I showed the children how it can be used to make creams and shampoos. They shared the recipe with the algueras and said: “Now you can earn more, because the products have a cosmetic use: it strengthens hair and skin.”

The children shared the recipe with the algueras.

You did something great with your fellow students.

Yeremy and his research team won prizes. They were invited to Santiago to present their inventions. On their first trip outside of San Sebastián, they landed in front of a bunch of officials at the headquarters of the DIBAM, Chile’s association of libraries, archives, and museums!

I prepared Yeremy for the meeting: “Hold your head up and don’t look at the ground. Be proud and say: ‘I’m Yeremy from San Sebastián.’ Speak softly and with a clear voice. You did something great with your fellow students, not everyone gets to come to Santiago and tell people what they’ve done.” Yeremy was a different person after that.

It gets proven time and again how important STEM education is for developing empathy, increasing confidence, and developing the ability to communicate.

Yeremy has already finished the fourth medio class (final year of secondary school) and now studies at university. His story shows how important it is to listen to students to build upon their curiosity in STEM subjects. This gave Yeremy a completely different perspective on his future.

His story shows how important it is to build upon the curiosity in STEM subjects.

Experimento Blended

At the beginning of 2021, I received the invitation from PUCV to become part of the design team for Experimento Blended. I immediately said yes. The project is fantastic: I work with colleagues from Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru. Before we started, we took part in a regional survey on practical experiences in STEM lessons that incorporated the participants’ own content development ideas in addition to what was outlined in Experimento. More than 650 teachers contributed to creating a complete overview of teaching and learning practices. This formed the foundation for the Experimento Blended modules, which focus on making analog and digital lessons possible in a range of different contexts.

I’m bringing all of my experiences from virtual STEM lessons with Experimento into my work on developing Experimento Blended. We have the opportunity to go much further that creating content – analog or digital – for the blended concept: it’s also an incredible chance to incorporate inclusion into the modules.

We know that STEM education is particularly helpful and encouraging for students with special needs, such as those with learning disabilities. This should absolutely be integrated into Experimento Blended.

September 2021

STEM Education for Innovation

Together with partners in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru, we adapt STEM teaching and learning content for digital use in the classroom. The initiative is supported by Siemens Caring Hands e.V. and the German Federal Foreign Office.